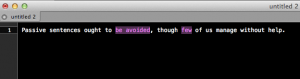

Two months ago, I downloaded and installed a writing tools bundle for TextMate 2, one of my favorite text editors. “English Highlight” as it is so innocuously named, does three awesome things:

- It highlights weasel words (few, very, fairly, quite, etc.)

- It highlights passive sentences (or, should I say, passive sentences are highlighted)

- It highlights duplicate words (not not that you’d ever do that).

Christopher Alfeld’s “English Highlight” is an adaptation of Matt Might’s shell scripts. Matt Might is an Assistant Professor at the University of Utah. He noticed that his students tended to ‘abuse’ the passive voice, use weasel words, and repeat words, so he wrote some bash scripts to identify these and integrated them into their LaTeX build. This has spawned a variety of plugins for common text editors. I’ve complied a list of plugins at the bottom of this post.

I am not going to lie: it was demoralizing when I first opened up a file and saw tons of purple. Apparently nine years of post-secondary education (6 of which were in the sciences) bred a deep love of the passive voice. Similarly, two years of graduate school, where the answer to every question is ‘it depends’, may have left me generous with my ‘various’, ‘numerous’, and ‘few’s. Highlighting my shortcomings in purple makes it easy for me to identify areas that need work, and to quickly make my writing stronger and clearer.

Weasel Words

The thing about weasel words is that they rarely add to a sentence: they either make your sentence vague or unnecessarily wordy, neither of which is a positive. Admittedly, sometimes you want to say that something is ‘quite’ something. That’s cool! You’re allowed! You might not realize how often you say ‘quite’ or ‘very’, though, and if it’s not helping, it’s hindering.

I went looking for a wishy-washy sentence that I’d recently wrote, but couldn’t find one: it seems my highlighter has done the trick! I’m afraid to open any of my old research papers, so I’m borrowing an example from Matt Might:

Bad: False positives were surprisingly low.

Better: To our surprise, false positives were low.

Good: To our surprise, false positives were low (3%).

I know I have a tendency to overuse ‘various’, ‘numerous’, and ‘fairly’. Highlighting those words draws my eye back to the sentence and makes me think about ways I can improve it. Often it’s as easy as deleting the word.

Passive vs. Active Voice

The passive voice thing is less straightforward than the weasel words. The passive voice has historically held a hallowed position in the sciences, where the prevailing opinion seems to be that science should mysteriously emerge completely independent of the scientists who do it. For this reason, students have to write “10mg of magnesium were massed” in their lab reports, rather than “I massed 10mg of magnesium.” This may have been a contributing factor in my changing majors from chemistry to environment, where I was occasionally allowed to write as though I existed.

During the aforementioned environment undergrad, I attended a somewhat rebellious lecture by Linda Cooper. Linda Cooper is a lecturer at McGill who studies science communication and teaches classes on science writing. She argued that using “direct, active-voiced sentences” makes sentences stronger and easier to read, and that we should all stop blathering on endlessly in the passive voice and instead, choose to use the active when appropriate. It’s easy to see that she’s right when you compare passive-voiced to active-voiced sentences:

Original: If MMS is being run with DB Profiling enabled, further permissions are required.

Revised: If MMS is running with DB Profiling enabled, the user requires additional permissions.

While both sentences point to the same concepts: that running MMS with DB profiling means you’re going to have to do something with permissions, the first sentence is far more vague. What sort of ‘further permissions’ are we talking about? Permissions for MMS? Permissions for you-the-user? Some sort of network permissions? Who knows! The second sentence get to the point: the user requires additional permissions. In either case, the next paragraphs describe what those permissions are, but the revised sentence guides the reader more quickly to the correct answer.

There’s certainly times where passive sentences are appropriate: for instance, I haven’t managed to rewrite “MongoDB is designed specifically with commodity hardware in mind…” as an active-voiced sentence, and I doubt I will. Expunging all passives from the record isn’t the goal here: the goal is to write as clearly as possible, and to be more aware the choices you make when writing.

Resources

As mentioned above, Matt Might’s scripts have been adapted for a number of text editors. I particularly like the name of the emacs / vim mode. If you’re doing any sort of writing – technical or not – I highly recommend installing one of these extensions and trying it out. It makes a huge difference.

- emacs: Writegood Mode by Benjamin Beckwith

- vim: Writegood.vim by David Beckingsale

- TextMate 2: English Highlight by Christopher Alfeld

- Sublime Text 2/3: Sublime Writing Style by ‘thedataking’. I’ve not yet tried this one out as one of my personal projects is to figure out how to write my own package, so your mileage may vary. It’s now available on package control, as well, yay!